...there is no more fruitful source of family discontent than a housewife's badly-cooked dinners... Isobella Beeton (1861)

Its easy to think of the 19th century as the "dark Ages" where people still lived in caves at least in comparison to our lives today. Actually, the 19th century was the Victorian Age and was quite enlightened.

And while you might think that cooking consisted of following family recipes that were handed down through the ages, the truth is -- cookbooks were as popular then as they are today.

Best selling cookbooks every year

In fact, there were over 100 popular or "best seller" cookbooks published during 19th century, that's one best seller per year on average, and countless smaller books whose numbers are probably in the hundreds.

Popular authors of the time included Catherine Beecher, Sarah Hale , Alexis Soyer, Charles Francatelli, Eliza Acton and Isobella Beeton. All had loyal followers.

While Soyer and Francatelli were managing the finest of victorian kithens, between 1830 and 1865 women such as Margaret Dodd, Mrs Rundell, Eliza Acton and Isobella Beeton were writing the domestic bibles of the time.

Household management was a serious subject in those times, and many cookbooks combined tips and instructions for managing the house, serving guests, setting tables and dressing wild game.

What else did you find in 19th century cookbooks? Why recipes of course and many of them are still popular today although the preparation method might have changed.

Today most people reading a modern cookbook see a recognised format, first the list of ingredients and then the steps describing the preparation. More often, recipes in the early 19th century had no such list, and instruction for cooking times or temperatures were, by todays standards vague.

Eliza Acton in the 1840s was one of the first to list recipe ingredients and method separately. Twenty years later Mrs Beeton adopted a simlar style listing ingredients, mode, time, average cost, number of persons and seasonality. (Berriedale-Johnson. M. 1989)

Beyond recipes, some cookbooks even provided pharmaceutical advice including cures for warts, bee stings, coughs and colds, hairloss, toothache, nosebleeds and cracked lips .

The following recipe, taken from Francatelli's Cook's Guide is called;

A wash to prevent the hair from falling off.

"A quarter of an ounce of unprepared tobacco leaves, two ounces of rosemary, two ounces of box leaves, boiled in a quart of water in an earthen pipkin with a lid, for twenty minutes; strain and use this wash cold, by applying it to the roots of the hair with a hair-brush occasionally during the summer months."

Cookbooks of the 19th century were written with the stoves, food choices and cooking utensils of the day in mind. There was very little "instant" on the menu and even the most basic dishes were made from scratch.

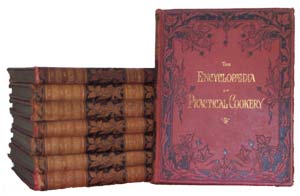

Garrett's Encyclopædia of Practical Cookery (1890s)

In the 1890s Garrett published the Encyclopedia of Practical Cookery. Much sought after today this monumental two, four or eight volume encyclopeadia contains more than two million words on the art of cookery and table service.

Long and descriptive cookbook titles were the fashion in the early 19th century Mrs Rundell's book appeared as "A New System of Domestic Cookery, formed upon Principles of Economy and adapted to the Use of Private Families"

So how different are recipes from then compared to those of today? Some of them don't seem very different at all. Except for the odd usage of a word here or there, this recipe for oyster stew could have been snipped from last Sunday's newspaper:

“Open the oysters and strain the liquor. Pat to the liquor some grated stale bread, and a little pepper and nutmeg, adding a glass of white wine. Boil the liquor with these ingredients, and then pour it scalding hot over the dish of raw oysters. This will cook them sufficiently.

“Have ready some slices of buttered toast with the crust cut off. When the oysters are done, dip the toast in the liquor, and lay the pieces round the sides and in the bottom of a deep dish. Pour the oysters and liquor upon the toast, and send them to the table hot.”

Sounds like something I could do, but the soggy toast part might be a bit too much for me. Anyway, cooking was an art form then as it is now and 19th century cookbooks are a real treasure to read. Try one and see for yourself!

Sources M. Berriedale-Johnson, The Victorian Cookbook (1989) • L. Jackson, The Victorian Dictionary, 29 Sept 2005, <http://www.victorianlondon.org/>